Lover Earth

We often refer to the Earth as our Mother Earth, and in this way of relating project a whole bunch of attitudes towards Earth that we might project upon our own mothers. What if we imagined the Earth as our Lover instead? How could this conjugal style of relating transform our interrelationship with this sacred planet?

The Rewilding Wheel: Turning Towards Transformation

The Rewilding Wheel is a sacred circuit that seeks to locate the wisdom of universal nature symbols within one’s particular homescape for the purpose of spiritual formation. Rewilding Community member Lisa has been journeying around the Rewilding Wheel for over a year. Read this thoughtful interview that provides insight into the seasonal practices that can lead to a deeper relationship with the Sacred Wild.

Rising Rooted: How Creation Theology Roots Us in Belonging

A good Creation Theology will be a decolonized theology that is climate-focused. This post originally was a sermon delivered to Lake Burien Presbyterian Church in September 2019, and responds to the question: How does our faith flourish while our forests burn?

Waymarkers: Categories of Inspiration

As I have more opportunities to teach and accompany others on their soul-formation path, I am often asked what are the areas that have most influenced my work and Waymarkers’ offerings. As I was clearing out my office recently, I came upon a writing project and drawing that aimed to get at three primary categories of inspiration and influence. I created this in October 2015 and it is amazing to see how these categories continue to shape and form my thinking and my work!

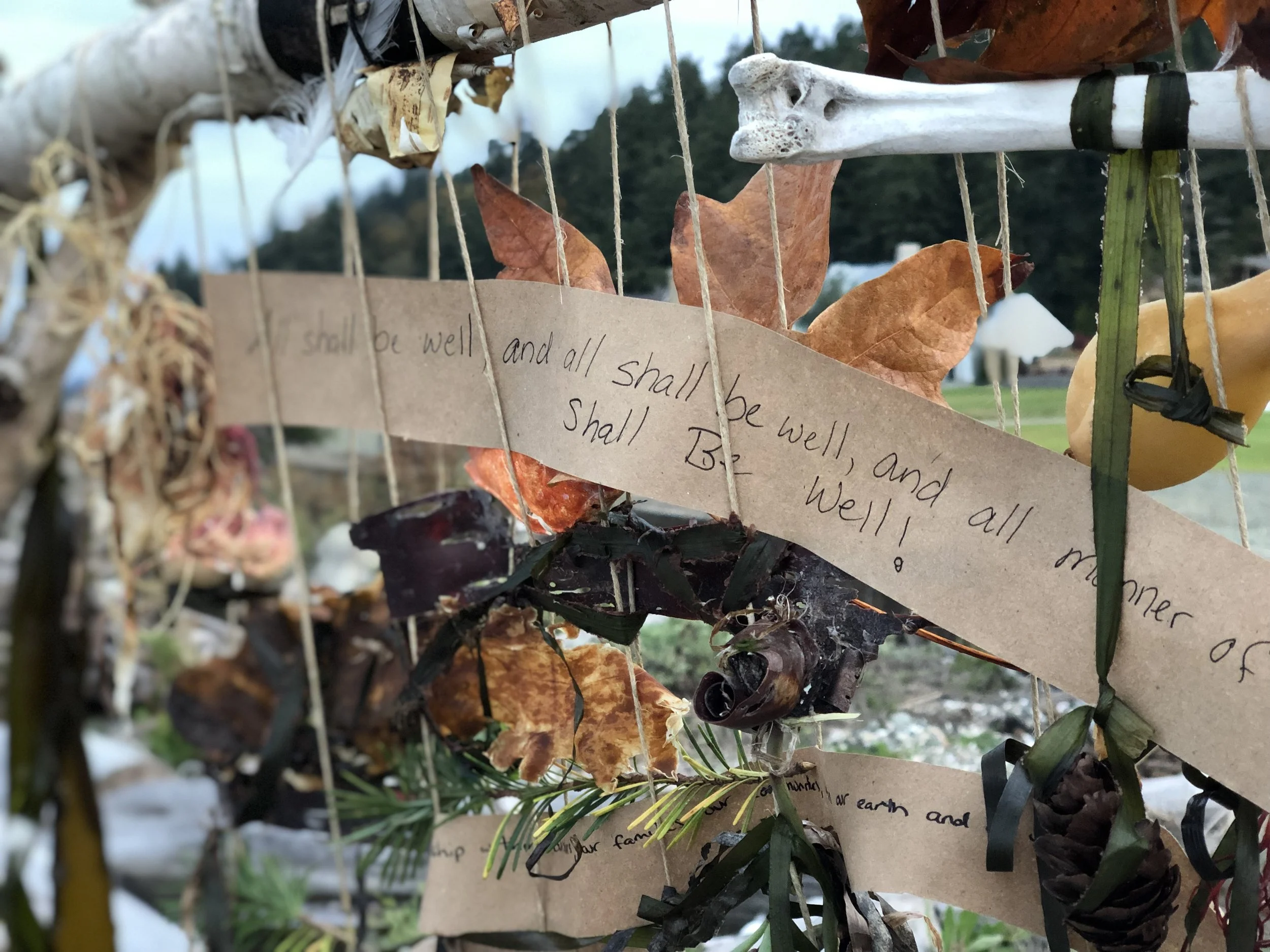

Autumn Rewilding Retreat | Reclaim the Skin You are Meant to Be In: How Stories of the Selke Guide Our Becoming

An immersive Rewilding Retreat weekend wetted with myth, soul ceremony, ritual, and wild wanderings was just the thing for a group of courageous women who willingly engaged the Celtic story of the Selkie as a way to re-cover and re-member their meant-for-ness.

Summer Rewilding Retreat: Scraping the Ground for the Grief Seeds

My Rewilding Year continues and comes to completion with time spent within the associated energies between the Summer season, Southern direction, and Earthen element. Combined, this wisdom resides in the bioregion of the farm, the garden, the field. Read on to learn along with me what I recovered when I spent time with Dr. Randy and Edith Woodley at Eloheh Farm in the Willamette Valley in Newberg, Oregon.

Listening in Place as Practice & Poetry-A Workshop with David Whyte

“The Practice & Poetry of Listening in Place” was the title of the workshop I was invited to facilitate with the poet, writer, and philosopher David Whyte. From this starting place, we drew upon themes of the selva oscura, the dark woods, and how the path is both guide and our truest selves. Participants were given native plants to get to know and with whom to co-create nature mandalas as a practice of listening to, and learning from, the more than human world. It was an extraordinary day!

Rewilding as an Act of Remembering

While I have loved well my garden and all the growth that has occurred through the process of cultivation and design, I have found in recent years a deep and demanding need to leave the order of the garden, to see it as a threshold inviting me beyond to the forested fringes or the wisdom found within wild waters. I have desired prayers and practices, rites and rituals that would remind my bones that I am related and dependent upon beaver, bluff, and bird, and how they fare becomes a litmus for my own wholeness and wellness. This kind of wholeness which balances on an ecosystem approach, can only be gained by a journey that takes one deep into the woods, through fields, tracing watersheds to the sea, and climbing up to the high climes of the mountains.

Rewilding & Journeying with Nature: A Conversation with Pilgrim Podcast

Are you curious about how I understand rewilding as a spiritual practice and nature as a sacred guide? Are you wondering if a Rewilding Retreat is right for you? Listen in to this illuminating conversation I had with Lacy Clark Ellman, host of the Pilgrim Podcast and pilgrimage guide with A Sacred Journey. I think you will come away with a desire to be rewilded!

Rewilding Prayer: How Caim Invites Protection for All of Creation

This week my youngest son started pre-school. And while his mornings will be spent within woodland walls and upon forest floors at a nature preschool, both he and and I were experiencing a deep anxiety around this fundamental shift in our daily rhythm together. I awoke early on his first day of school for a time of meditation and prayer practice on our behalf and for personal preparation.

I began with an embodied, ritualized form of prayer, the Celtic circling prayer.

Guidance & Wisdom from the Sacred Wild

I feel like I've been walking towards today for years. It was four years ago that my work with Waymarkers was put in the vault as I left to pursue my Masters in Theology & Culture with a focus in eco-theology from The Seattle School of Theology & Psychology.

This journey took me through some of the most wildest of woods where I was taught again and again of the revelatory quality of the natural world, and that the woods are indeed the wisest of teachers. I reflect on themes experienced in these last years during the commencement speech I was asked to give during my graduation ceremony. You can listen to that here.

Emergence

This is merely a note to awaken you to what is emerging here at Waymarkers. I graduated with my Masters in Theology & Culture from The Seattle School of Theology & Psychology and a specialization in Thomas Berry's Universe Story from Yale University this past June. Waymarkers is soaking this up and becoming a sacred guide, a presence that will take us deeper into the wilds where Creator can be heard speaking through all created things.