Discerning The Call That Knocks on Your Door

Questions that I am often asked about the invitation to make a pilgrimage journey are: “How do I know if this is really The Call knocking on my door?” “How do I know if this just isn’t a mood or a distraction from my responsibilities?” There are, fortunately, ways to tell. The great mythologist Joseph Campell who did extensive work around the idea of the monomyth, or the hero’s journey, notes four experiential qualities that accompany The Call. Do these resonate with you?

The Return: How Returning Home Requires An Open Door

Our personal pilgrimage journey is global in both scope and impact, and we are invited to transformative micro-practices that overhaul how we view our homescapes. Our return requires us to leave the door open to the world just beyond its threshold, maintaining a posture of looking out for opportunities to give of our gained wisdom and our boon of blessings.

Pilgrimage: It Grounds You

Through the archetypal movements of pilgrimage, one finds deep meaning and spiritual connection through both the exilic wandering and the renunciations associated with the journey; moreover, as a result, one finds themselves deeply connected within the community of creation, and profoundly rooted and at home in their pilgrimage place.

Pilgrimage: A Profound Act of Listening

I absolutely believe that one might need to journey to a holy place on the other side of the planet to recover this renewal. And, sacred sites are also all around us, quietly remaining in the more wild edges of our frenetic lives, awaiting being noticed, remembered, attended. The pilgrimage process is one that can be engaged just as much at home as abroad and with just as much potential for transformation. It is the profound act of listening, which transforms the average elements of a place or even just your normal mid-week day, into a pilgrim's portal: a way of sensing and seeing that transmits the sacred to and through the greater community of things that surround us!

Solvitur ambulando. It is solved by walking.

In sacred travel when the pilgrim mood is awakened and engaged, every experience is potent and portends a deeper meaning; every contact attests to some greater plan. No encounter is without sacred significance.

Pilgrimage Demands Your Presence

Iona is sacred land and people make pilgrimage here to soak of these stories, hoping that something of this sacred soil will stick and have a profound impact on their personal lives. And my hunch is that there are many more sacred sites all around us, even in our own urban neighborhoods, if only we would pay attention.

Go. Deliberately.

What might have started as a soft whispered call has now become a heart-throbbing desire to go and find the animus mundi--the Soul of the world! Pursue the wild place that makes your heart skip both with doubt and desire for here is where you will find your Answer covered in salty barnacles and cracked-leathered edges and God within the windswept moors and tangled trees.

Pilgrimage Awakens the Soul

There is an urgent restlessness and a deep seeded remembrance to come home to our true selves, a deep longing for an integration that braids the soul, the soil, and the sacred. This longing, this soul-solicitation-asking initiates the seeking process, as it is inherently true that you cannot cultivate an integrated home-space for your soul unless you first have intentionally gone out and away from all that you know and are comfortable within. Will you go?

Rewilding & Journeying with Nature: A Conversation with Pilgrim Podcast

Are you curious about how I understand rewilding as a spiritual practice and nature as a sacred guide? Are you wondering if a Rewilding Retreat is right for you? Listen in to this illuminating conversation I had with Lacy Clark Ellman, host of the Pilgrim Podcast and pilgrimage guide with A Sacred Journey. I think you will come away with a desire to be rewilded!

The Treasure: How Pilgrimage Cultivates a Connection to Place through Permanence

I am thrilled to be preparing to deliver a paper at William & Mary College next week at their annual symposia on Pilgrimage Studies. In many aspects, this opportunity feels very much like a pilgrimage journey in and of itself. A couple years ago I received an invitation to submit a proposal for this particular academic gathering, which very much felt like the call, the requisite summons of any meaningful pilgrimage. However, life circumstances prevented the manifestation of that opportunity until now. And so I have the opportunity to seek the wisdom gained these past couple years as I have journeyed through the descent, the time of darkness and disintegration that occurs when a journey is truly leaving its indelible mark on you, and prepare for my arrival.

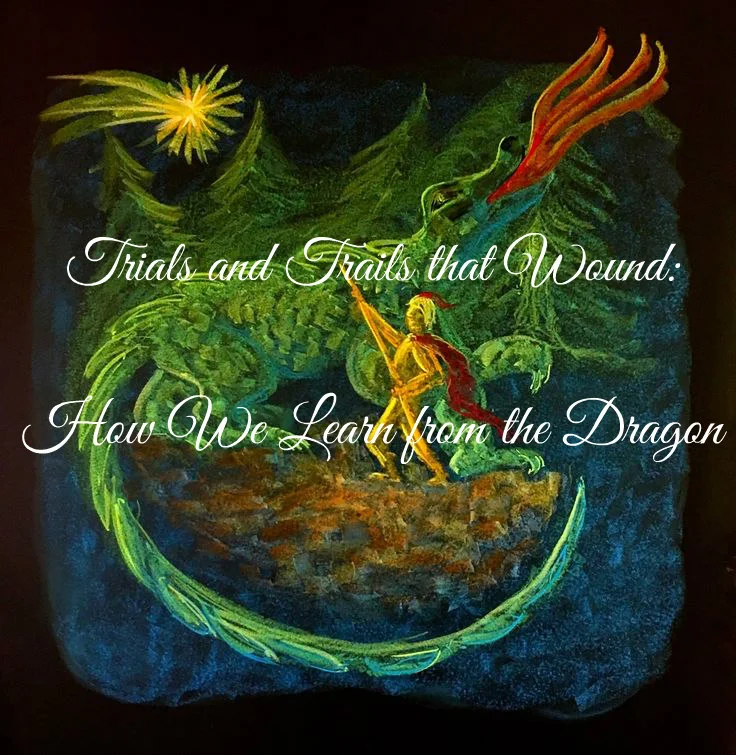

Trials and Trails that Wound: How We Learn from the Dragon

We are coming into the season of Michaelmas, the ancient festival time of St. Michael who is connected to myths and lore around harvest abundance and more prominently, dragons. St. Michael is an archetypal representation of our inner light and courage that is called forth when scarcity is nigh. This scarcity and its corresponding fear is our dragon, one that we all must meet.

Yes, dragons and the dark woods within which they live, can scar us. But instead of killing the beast in return, can we learn to ride the dragon, and see our scars as sacred?

Guidance & Wisdom from the Sacred Wild

I feel like I've been walking towards today for years. It was four years ago that my work with Waymarkers was put in the vault as I left to pursue my Masters in Theology & Culture with a focus in eco-theology from The Seattle School of Theology & Psychology.

This journey took me through some of the most wildest of woods where I was taught again and again of the revelatory quality of the natural world, and that the woods are indeed the wisest of teachers. I reflect on themes experienced in these last years during the commencement speech I was asked to give during my graduation ceremony. You can listen to that here.

Iona: Getting There Well

The journey itself to Iona makes this place unique; it is long, quite complicated and even relatively uncomfortable for the urbanite who is accustomed to quick and easy travel. This distance provides the perfect pilgrimage process, for it truly requires a removal of oneself from all that is familiar and supplies a lengthy trek-full of obstacles, no doubt! Once there, one finds a sparsely populated island, with almost no cars and a large abbey, whose structure appears to have dropped from the heavens onto this topographically small and relatively insignificant place. Sheep outnumber the residents and the sunlight plays on the hillsides in the most magical ways. One senses almost immediately Iona is indeed a "thin space" – that brushing up against the Divine is inevitable.

Emergence

This is merely a note to awaken you to what is emerging here at Waymarkers. I graduated with my Masters in Theology & Culture from The Seattle School of Theology & Psychology and a specialization in Thomas Berry's Universe Story from Yale University this past June. Waymarkers is soaking this up and becoming a sacred guide, a presence that will take us deeper into the wilds where Creator can be heard speaking through all created things.

Set out. And seek Wisdom, not advice.

"When setting out on a journey, do not seek advice from someone who has never left home." -Rumi

Iona Pentecost Pilgrimage: An Island Between Heaven and Earth

The Sacred Island of Iona is riddled with fables, legends and lore. Around every bend you encounter places that are linked to a history deeper than our own and stories that reverberate with both the whisking wind and the beat of angels wings. While we came here keenly aware of the mysteries that shroud this island, our time on Iona was strengthened by opportunities to pull apart the veiled sacred sagas and see behind the curtain the very real people and relationships that have curated all that Iona is known for today.

Iona Pentecost Pilgrimage: Island Journey

The pilgrimage around Iona visits places of sacred significance and historical importance on the island. There are 18 sites in all and can take nearly all day to get to each one. Our group broke the pilgrimage up in a few days-hitting the Abbey's specific spots while we did our tour and hiking up Dun I on a quiet afternoon-so that we could enjoy the heft of the hiking down to the south end of the island to really spend some meaningful time at St. Columba's Bay and enjoy the reflections at holy sites along the way.

Iona Pentecost Pilgrimage: When in Rome...

A fundamental aspect of pilgrimage is to engage the local culture of a site. It is paramount to experience with your senses the place where you are. This means intentionally involving the sight, sound, smell, savor and sensations of a place. It is advisable to not just find a McDonald's or Starbucks when you are hungry or thirsty, but seek after local cuisine and appreciate it for the expanding understanding it gives you for a locale. It means taking out the earbuds and listening for the unique melodies that are native to a particular place; this could be the sounds of the sea, regional birdsong, or the lilt of a distinct accent. And it is certainly seeing the sights that enhance the definition of a place.

Iona Pentecost Pilgrimage: Solviture ambulando

Here on Iona, where it is often stated in promotional material that sheep outnumber people and cars, everyone walks. There is but a single road and upon that one walks to get to the ferry, get to the Abbey, get a cup a tea. It is both a means to a destination and a value in and of itself. The road becomes a liturgy and walking the prayers.

Iona Pentecost Pilgrimage: Arrival-Hospitality

The warm invitation that this island, and its people, extend to new comers is quite profound. There is a very real sense that there are no strangers in our midst. In the context of the single road, the hostel or the beaches, there are ready smiles to lift yours, gregarious laughter rushing out to include you, and generous invitations to share tea, a meal or a bit of chocolate. There is a sense of general community and conviviality that spans generations and gender.